Little Symbols, Big Difference

If you’ve ever browsed the aisles of a grocery store, chances are you’ve passed by a few dozen registered trademark symbols without even noticing. Look around right now, wherever you are. Is there a can of Coca-Cola sitting on your end table? A bottle of Advil there on your desk? Are you drinking water from a Nalgene water bottle? Any of these items will bear the subtle but familiar ® denoting a registered trademark of the brand. This is the symbol you can (and should) use once your trademark registers with the USPTO, whether it is a word mark or design mark and whether it is for goods or services. It establishes “constructive knowledge” of your registration and helps protect your trademark rights, notifying customers and competitors alike that you hold a federally registered trademark and unauthorized use of this mark constitutes trademark infringement.

If your trademark is not yet registered, you cannot use the ® symbol in association with your mark, but you do have the option (which you should take) of using ™ (or ℠ for service-only marks) to claim common law trademark rights. ™/℠ does not signify the same level of trademark protection, just like common law rights are not equivalent to a federal trademark registration, but this is a way of publicly demonstrating your claim to a mark while it is [hopefully] on its way to registration.

In either case, whether your mark is registered or not, the symbol you use should appear in the upper right-hand corner of the mark (DRUMM LAW®) or, if that will look strange, as may be the case with some design marks, the lower right-hand corner.

Wondering what the little © and ℗ symbols mean and how they factor into all of this? © denotes a registered non-audio copyright, while ℗ is the “phonographic copyright” symbol, or the symbol used especially for audio copyrights such as music and audiobook recordings. So you won’t be using these in conjunction with your trademark unless it is the name of an artistic work for which you also hold a copyright.

It’s important to note that, when it comes to international commerce, many countries have different and specific rules and regulations surrounding the use of these symbols, so if you are considering an international trademark, or just distributing your goods to other countries, it may be wise to consult with a trademark attorney first.

Trademark vs. Copyright: What's the Difference

When creating a new product or service, or even forming a new entity, understanding the differences between trademarks and copyrights can be vital.

The first step is really a simple one: it’s important to find the right trademark lawyer for you. At Drumm Law, we’re proud to offer attorneys with expertise in the area of trademarks. We work with all of our clients to help them efficiently, and cost-effectively, setup their businesses and position them to be the most successful versions of themselves.

“A lot of times, (people) misuse the word copyright, like ‘I want to copyright my brand,’” said Mike Drumm, attorney and founder of Drumm Law. “One of the most clever sayings in the world is “I want to protect (my brand). A trademark protects a brand, copyright protects you from copying a product like music or a book.”

In short, the difference between trademarks and copyrights, although seemingly confusing, can be simply conveyed as this: trademarks protect commercial names, phrases and logos (i.e. the name of your beer and the logo of your company). Copyrights generally protect creative works (i.e. the design of the label on your beer). While both may be important, it’s the trademarks that are of the utmost importance for breweries.

“Trademark is, ‘I have a brand and you can’t have a brand that looks like mine,’ but copyrighting is protecting something you created — not the idea,” Drumm added.

About Drumm Law

At Drumm Law, we offer an experienced team of trademark attorneys, proficient in helping our clients:

- Select and file proper trademark applications

- Undergo trademark clearance searches

- Defend/file trademark application prosecution

- Monitor trademark usage and maintenance

- Conduct intellectual property audits

- And more…

Contact Drumm Law’s trademark lawyers to receive help with your trademarking processes at.

Why You Need a Trademark Insurance Extension

“Laughter is the best medicine, but your insurance only covers chuckles, snickers and giggles.”

We’ve all been there. Whether it’s buying AppleCare or upgrading insurance on your rental car, odds are you feel very strongly about whether additional insurance is worth it or not.

But… if you’ll give us a few moments of your time, we’d like to talk to you about trademark extension insurance. Seriously. We promise to keep this brief and not to call you during dinner, but an “insurance” extension is actually a serious consideration when filing an Intent to Use trademark application, and we really would like to discuss it.

So, what is this “insurance” extension? According to the USPTO, the purpose of an “insurance” extension “is to secure additional time to correct any deficiency in the statement of use that must be corrected before the expiration of the deadline for filing the statement of use.”

In plain English, if you filed a new application as Intent to Use, you must file a Statement of Use once you begin using the applied-for trademark in commerce (i.e. selling stuff). This shows the proof that you are using the trademark for the goods or services (those same ones you said you had an “intent to use” in your trademark application). If you have applied for a trademark before, you know that there is often a somewhat murky line between which specimens (samples showing use) are deemed acceptable and which are not.

An “insurance” extension gives you additional time just in case your specimen is rejected.

Worst case scenario: you apply for a new trademark as Intent to Use. The application is accepted and the USPTO issues a Notice of Allowance, giving you six months to produce and submit a specimen or file an extension request. You file the Statement of Use and the USPTO examining attorney issues an Office Action stating that the specimen submitted does not show use (this can happen for any number of reasons and ultimately relies on the personal judgement of the examiner). You now have six months to respond to the Office Action and submit a new specimen. But here’s the catch. If you take only one thing away from this article, let it be this: even though you have six months to respond to the Office Action, the substitute specimen needs to have been in use prior to the original six-month Notice of Allowance deadline.

Let’s quickly break this down. If you applied for an Intent to Use trademark and a Notice of Allowance was issued on June 14, you would have until December 14, 2019 to submit a Statement of Use with specimen. Let’s say you do this on November 1. But the trademark examiner deems your specimen unacceptable and issues an Office Action on January 23, 2020, giving you until July 23 to submit a substitute specimen. HOWEVER, that specimen must show use prior to the original December 14, 2019 date. If you are unable to produce a substitute specimen showing use prior to that original six-month Notice of Allowance deadline, your trademark application will abandon and you will have to file a new application and risk losing you trademark rights.

This is where the “insurance” extension comes into play, with the potential to save you stress and money. If you are at all unsure about your specimen, you can file a Statement of Use and extension request simultaneously. This will give you an additional six-month safety net if your specimen is rejected.

Going back to our hypothetical timeline: if you filed an extension request in addition to your Statement of Use on November 1, and the trademark examiner issued the same Office Action on January 23, that extension would grant you an additional six month window in which to fix any deficiency with the specimen.

Filing an “insurance” extension as a contingency plan is a fraction of the cost of filing a new application. The trademark department at Drumm Law will do whatever we can to make sure that the specimen you provide for the Statement of Use will be accepted, but it is impossible to know what the many attorneys at the USPTO will accept and what they will reject. Give yourself some time.

Email us at trademark@drummlaw.com and we would be glad to review the specimen you intend to use and, if you think it’s appropriate, talk to us about filing an “insurance” extension. The last thing we want is for you to waste money because your specimen was rejected.

** It should be noted that you are only allowed to file one insurance extension, even if you have not met your 36-month extension limit.

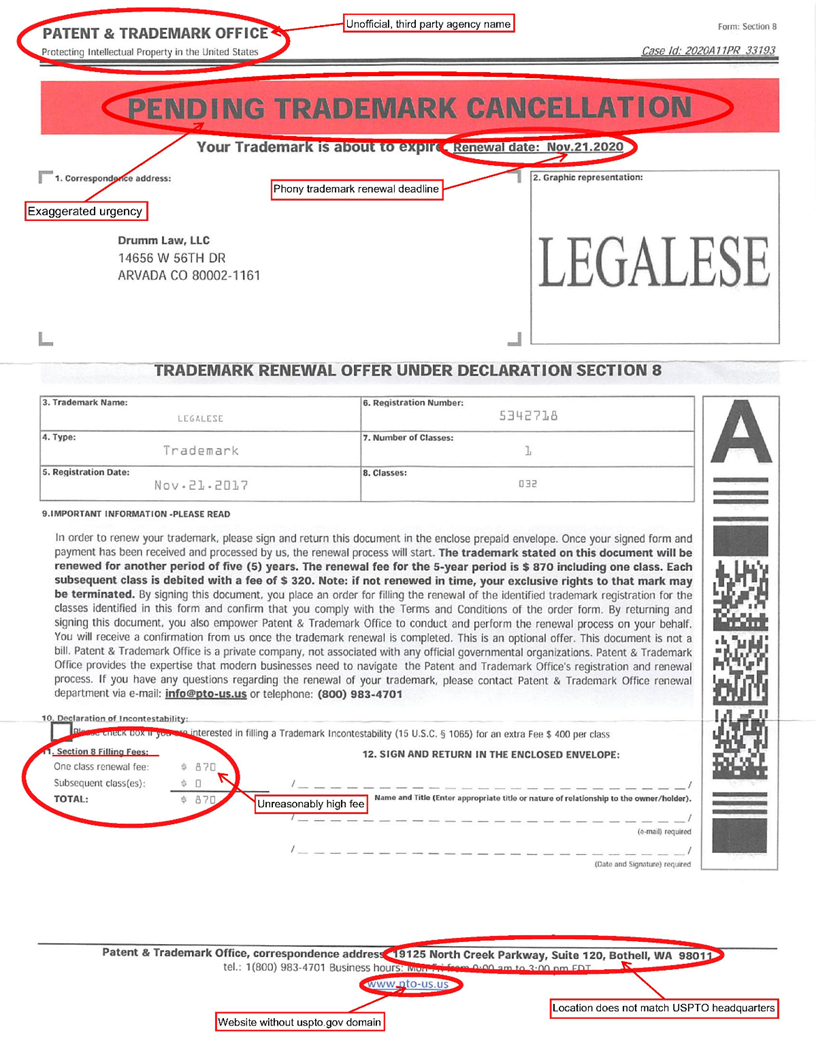

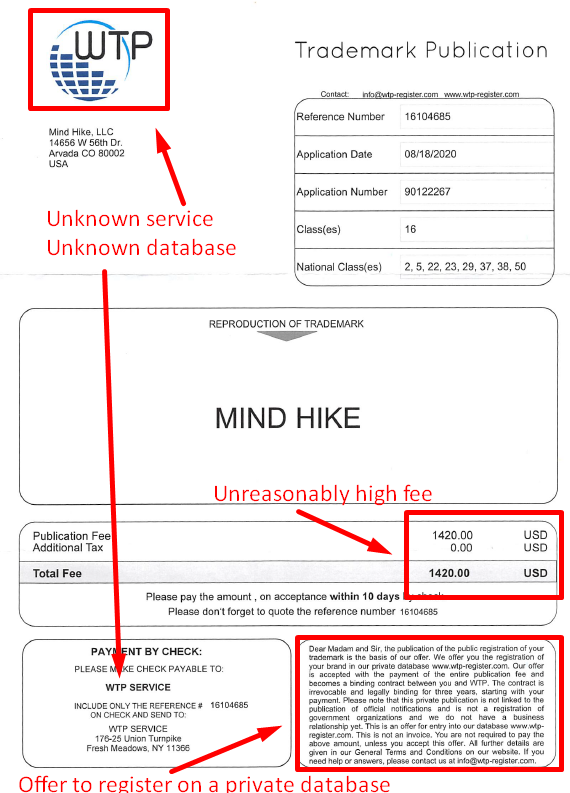

How to Avoid Trademark Scams

We have been trying to reach you about your car’s extended warranty…. a member of the royal family would like to transfer a large amount of money to you…. your Netflix password has been compromised, reset now… Does this sound familiar? Well now you can add another to the list. Harmful phishing schemes are everywhere these days and scams, or spam, that specifically target trademark holders are rising steadily. According to 2019 data, about 45% of the world’s daily email traffic is spam – that’s somewhere in the neighborhood of 14.5 billion spam emails globally every day. Add to these extraordinary numbers the ubiquity of mail fraud and you have a tricky landscape to navigate.

Misleading invoices demanding astronomical sums of money to secure your trademark on a private registry or to file a trademark renewal on your behalf are favored as vehicles to defraud trademark owners. If you have ever registered a trademark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) (or internationally with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) or European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO)), you are at risk of receiving fraudulent renewal notices, cancellation threats, or revival offers. Chances are you have already received at least one.

Because registrants’ addresses are publicly available, such solicitations used to come most commonly through the mail. These are no less alarming than the emailed variety, but easier to ignore in the digital age. That all changed at the start of 2020 however, when the USPTO instituted a new policy of requiring email addresses for the owner of an application. This rule was eventually amended some months later to not show the owner email address on the public record, so long as an attorney email is present. But this means that, for a several month period, owner email addresses were vulnerable public information, available at the fingertips of anyone with a computer, scammers included.

Whether it’s coming via inbox or mailbox, trademark scams are prolific. Any notice not originating from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, or your trademark attorney, should be treated as a scam. So, what can you do to keep yourself safe? Whether you are a Drumm Law client or just stopping by to read this article, if you think you have received a scam letter or email please contact us at trademark@drummlaw.com. We are more than happy to help you determine if the letter is real or fake.

Here are a few additional tools you can use to help mitigate the risks of falling victim to a trademark scam:

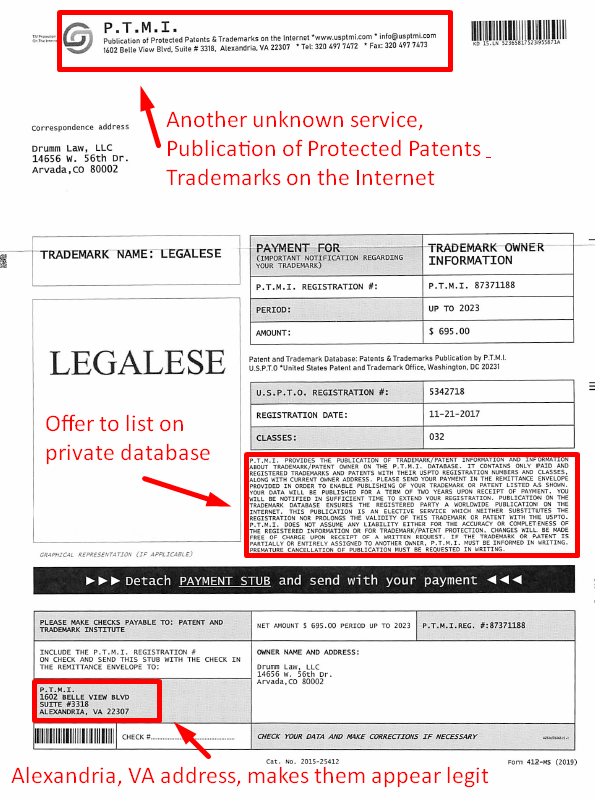

- Know what to look for. Unlike everyone’s favorite Nigerian prince, trademark scams are often subtle. You may receive notices that look legitimate, even to a discerning eye. Organizations like “Patent and Trademark Office,” “PTMI – Register of Protected Patents and Trademarks,” or “Trademark Compliance Center” all sound official at first pass, but don’t be fooled. Such titles will often be accompanied by a fictitious seal or a passably governmental web address.

Official letterhead of the United States Patent and Trademark Office:

Official seal of the United States Patent and Trademark Office:

Official seal of the United States Patent and Trademark Office:

Bottom Line: if it’s not from the United States Patent and Trademark Office in Alexandria, VA or the domain uspto.gov, it’s probably spam.

Bottom Line: if it’s not from the United States Patent and Trademark Office in Alexandria, VA or the domain uspto.gov, it’s probably spam.

- Know your trademark. Many trademark scams rely on a sense of urgency and provoke panic over losing your trademark rights. They will often feature headings - or a note on the envelope -such as “URGENT – open immediately!” or “Cancellation Notice.” These are frequently accompanied by either inaccurate or partially accurate renewal dates. The goal is for a recipient to make a knee-jerk payment for fear that their trademark will expire right under their nose. In reality, the USPTO offers a yearlong window for trademark renewal and a six-month grace period during which a renewal can still be filed with a late fee. Knowing what your real deadlines are can go a long way in weeding out spam surrounding your trademarks. If your trademark attorney isn’t giving you a heads-up about when your trademark is open for renewal, find an attorney that does. Send us a message; we will let you know if you have a deadline coming up.

Bottom Line: if a notice comes as a surprise, demanding immediate action for a rapidly approaching deadline, it’s probably spam.

- Know what to pay. While most law firms and online DIY services charge filing fees in varying amounts, many scams push the boundaries of what is believable pricing. The USPTO provides more useful information on trademark fees and how they are assessed here: https://www.uspto.gov/trademark/trademark-fee-information

Bottom Line: If you receive a notice requesting $800, $900, or $1,000+ for the renewal of one trademark in a single class, this is good reason for skepticism.

Not even an intellectual property law firm like ours is immune to deceptive solicitations. Below are three examples of recent scam letters we received. We have highlighted major red flags you should be on the lookout for.

Ultimately, the best defense against scams is hiring a trademark attorney – this will ensure that all updates and notifications from the USPTO will be funneled through them. They can help you remain vigilant against phony solicitations and offer valuable advice in other trademark matters, saving you money and stress in the long run.

What is a Trademark Disclaimer?

A disclaimer is a statement that indicates that the applicant does not have the exclusive right to use a specific word of a trademark by itself.

Disclaimers are required for composite trademarks (English translation=trademarks with more than one word or design marks with separate elements) for the portion of the trademark that is merely descriptive, generic, or geographic or it contains a company designation or a well-known symbol such as the dollar sign ($). The disclaimer statement indicates that the applicant does not have the exclusive right to use that specific word of the trademark when standing alone. The exclusive trademark rights exist in the entire mark. The reasoning for disclaimers is that these types of words and/or symbols are needed by other people and businesses to describe their goods and/or services. So no one gets to claim exclusive rights to these terms.

For example, if you tried to register a beer named Legalese IPA, you would probably have to disclaim the exclusive rights to “IPA”. The IPA element is descriptive and un-registerable by itself. While you would be able to stop other breweries from naming their beers Legalese Stout, you are not able to stop anyone from calling a beer an IPA.

Here are some famous examples of disclaimers:

STARBUCKS COFFEE – No claim is made to the exclusive right to use “coffee” apart from the mark as shown.

KIA MOTORS – No claim is made to the exclusive right to use “motors” apart from the mark as shown.

BURGER KING – No claim is made to the exclusive right to use “burger” apart from the mark as shown.

Trademark State Registration

I don’t distribute my goods out of state. Can I still trademark my names?

The short answer is YES!

The Lanham Act (also known as the Trademark Act of 1946) is the federal statute that governs trademarks. Generally, the Lanham Act requires that a mark is used in interstate commerce before it may be registered as a federal trademark.

Thankfully, interstate commerce is broadly defined.

Traditionally, interstate commerce has been focused on whether or not goods have physically crossed state lines. Due to the nature of modern commerce, travel, and the expanding reach of the internet, the lines for what is truly “local” has changed over the years.

“Use in Commerce” Within a State

Adidas (the shoe and apparel company) tried to trademark “ADIZERO” for athletic apparel (fun fact-one of the founding brothers of Adidas broke off and formed the shoe company Puma). The Trademark Office blocked this trademark because of a likelihood of confusion with the trademark “ADD A ZERO,” which was a clothing trademark owned by a church in Illinois for its fundraising campaign to encourage its congregants to add a zero to their donations (as in don’t give $10, give $100).

Adidas argued that the church’s marks were not in interstate commerce. The Illinois church defended the alleged non-use in interstate commerce argument by offering evidence that it had sold two hats bearing the contested marks to a parishioner who resided across state lines in Wisconsin. The sale occurred within Illinois, so the church did not rely on a sale made to a customer located across state lines at the time of the purchase. Adidas argued that the sale of two hats were “De Minimis,” meaning too trivial or minor to merit consideration for interstate commerce. Adidas won at the trademark court and the decision was appealed.

The Federal Circuit on appeal clarified the broad protection of the Lanham Act and reversed the trademark court holding. The Federal Circuit stated that the Lanham Act defines interstate commerce as all commerce which may lawfully be regulated by Congress.

The Federal Circuit held on appeal that the church’s sale of two hats showed that the marks were used in interstate commerce for Lanham Act purposes. The Federal Circuit Court held that the church was not required to present evidence that its sale of hats actually affected interstate commerce, or even to show that the hats were destined to cross state lines. Rather, the church merely needed to show that its sale activity, even if just local, fell “within a category of conduct that, in the aggregate” could exert a substantial effect on interstate commerce.

Say That Again Please (In English)

You make goods. Your goods are offered for sale. Out of state people may purchase said goods at your retail location or other locales. These purchases in the aggregate can affect interstate commerce.

Helpful Tips

Because the law (or the courts’ interpretation of the law) can change, here are some practical tips to ensure that you have interstate commerce goods:

- When you release new goods, make sure to get it on the worldwide web (whether through your own website or through the various social media channels).

- Encourage your guests to review your goods on the various review websites (odds are good you will have plenty of out of state reviews).

Clothing Trademarks

Ornamental Refusal? Wait… what?

Is your apparel graphic a “brand identifier” or just decoration? An ornamental refusal is when the USPTO refuses registration of your trademark because the specimen submitted with your application shows the use of your mark merely as an “ornamental” or decorative use on the goods and not as a trademark to indicate the source of the goods.

Trademarks are used to identify a product’s origin and tell you a bit about it - usually who made the product and a certain level of quality. In order to file a trademark for apparel, you must be using the proposed wording or design to identify that clothing as belonging to the trademarked brand, not just as embellishment. Logos, slogans, or branding that are exclusively decorative do not identify and distinguish goods and do not act as a trademark.

For example: a Ford logo can be used to identify a Ford truck. But that same logo on a t-shirt does not identify it as a brand of clothing (failing to indicate, for instance, quality, country of origin, etc.). Instead, this logo is being used as a decoration to appeal to people that like the Ford brand.

On the other hand, a polo shirt featuring the Lacoste crocodile on the breast creates the impression of a trademark - identifying the brand as that of the French clothing company Lacoste.

On the other hand, a polo shirt featuring the Lacoste crocodile on the breast creates the impression of a trademark - identifying the brand as that of the French clothing company Lacoste.